Decoding how banks create money and how access to high yield products by Fintechs impacts small-mid sized banks

In my last post on the SVB crisis, I touched briefly upon the fractional reserve or money multiplier theory but it was not too pertinent for what had happened to SVB and the other banks that went under.

That section of the post stemmed from the following comment from Frank but that can be extended to almost everyone who probably has taken Econ 101 and come to truly believe the money multiplier theory.

George Selgin alongside many others highlights 3 wrong theories of bank money creation:

(1) An ordinary bank must wait for reserves (deposits) to come its way in order to make loans; if they seem to maintain an 5% reserve ratio, then they can only lend 95% or deposits received.

(2) An ordinary bank can create money equal to a multiple of reserves (deposits) received. So if it receives X dollars and maintain 5% reserves, it can lend 20 times

(3) An ordinary bank can create money "out of thin air," with no need to either possess or to acquire funds by which to finance loans it commits to make, and hence no need to worry about either its actual reserve or the cost of securing funds from elsewhere.

I aim to target each of the points above in the sections to come and explain at an elemental level on how money is created by banks aka credit creation theory. This was broadly understood to be the case for nearly a century until the money multiplier theory took over in the latter half of the 20th century. The Great Financial Crisis of 2008 and the quantitative easing that followed caused a resurgence with Bank of England, Federal Reserve, and Deutsche Bundesbank publishing papers highlighting the role of banks in creating money.

Finally, in closing, I want to specifically highlight the SMB neobanks that over the past 18 months have worked on democratising access to rates that track the rates set by Central Banks. This echoes the developments in early 80s in U.S with the launch of Money Market Funds and the regulatory changes that followed allowing banks to compete with such funds. With a focus on small/mid sized banks, I highlight the potential risks they face from Fintechs especially around growth/profitability.

What is Money?

Money has been classically known to serve the following functions -

Store of value - Have an ability to retain value over time

Unit of account - Ability to price goods and services

Medium of exchange - Desire for people to hold it in expectation that they will be able to swap for a good/service later on

The way I have come to see money is to encompass all 3 functions and think of it as no more than an IOU. Every person has needs whether it is around saving, spending, investing etc and as society has come to encompass interactions that cross borders, money has come to become the institution that has solved for the lack of trust.

With the complexity that has been driven into the Financial Services sector over the past two centuries, money nowadays can be classified in several ways. This is pertinent for the discussion especially around bank deposits that people hold have come to play a major role in the total money supply.

Central bank reserves which play a critical role in the settlement process between banks and make up a significant portion of Base Money can be defined as

Overnight balances that banks hold in an account at the central bank. As such, they are a claim on the central bank. Together with banknotes, reserves are the most liquid, risk-free asset in the economy. And they are the ultimate asset for settling payments; banking transactions between customers of different banks are either directly or indirectly settled through transfers between reserves accounts at the central bank”

Broad money especially over the past century is where Banks have come to play an important role. My view is that banks have come to embody and function around fulfilling 3 main functions/jobs -

Maturity Transformation

Money creation(more implicit and not a direct mandate)

Over the past century, banks have come to serve as arms of Central Banks and enable them to pursue its monetary policy(again, something implicit and what the situation has come to be)

For those who are not familiar with what Maturity Transformation entails, here is how I tried to describe it in my last post

Having solved the problem of how money is created, let’s extend this to what happens after that. In a complex world of financial services with thousands of banks, deposits moving across all these banks as consumers of deposits buy services and pay others, this means that there is an imbalance of the loans that the bank has generated vs the deposits it might find itself holding.

I talked about how Net Interest Margin is the core of what the bank is focussed on. Deposits being IOU of the banks can be called upon at any point and hence are very much short term liabilities of the bank. There are ways where this can be turned into long term by locking away deposits via products but let’s ignore that for now. On the Asset side, especially as we consider loans and mortgages, in U.S 30 year mortgages are the norm. Loans in general are much longer in duration.

Maturity Transformation therefore is an inherent feature of the banking industry. They invest in long term loans which are assets but on the opposite side of the balance sheet, find themselves funding these via short term liabilities. The biggest risk in engaging in such a business is the interest rate risk that comes with the duration mismatch. Managing that is what bankers get paid for!

A key component of Maturity Transformation process are the loans that banks create which are usually longer in duration vs deposits that form majority of the liability side of the balance sheet. In a simplistic view, the table below highlights how different scenarios play out and the potential impact on bank profits.

The general view is that banks are basically in the business of financial intermediation and have built up a marketplace but where 2 sides don’t really interact with one another. By sitting in the middle, banks gather money by attracting consumers/SMBs/enterprises with either a return on those deposits or through cross subsidisation of other products.

Between approximately the 1930s and the late 1960s, the dominant view was that the banking system is ‘unique’, since banks, unlike other financial intermediaries, can collectively create money, based on the fractional reserve or ‘money multiplier’ model of banking. Despite their collective power, however, each individual bank is in this view considered to be a mere financial intermediary, gathering deposits and lending these out, without the ability to create money. This view shall be called the fractional reserve theory of banking.

Frances Coppola who’s writings I have come to really admire wrote the following

QE is widely misunderstood. Many people perceive it as some form of bank bailout, and are angry that banks haven’t “lent out” this money. The Bank has overseen important academic work into the way banks work and the reasons why banks don’t “lend out” QE money, but has failed to inform the public effectively about how QE works.

I perceived this as indirectly highlighting how prevalent is the idea of banks as being middlemen. Not only does the general public have a mental model that strongly revolves around this idea but the regulators through their QE policies(which a lot of people in hindsight have come to see as not having been too effective and having caused massive asset price spikes which did not really benefit the general populace) were misguided on how to get the economic engine humming.

The alternative explanation to fractional reserve theory and what really happens at banks is what is broadly known as the credit creation theory of banking. The overarching idea is that banks/banking system given the regulatory advantage they hold vs non-banking institutions are responsible for creating deposits. Deposit creation happens whenever the bank decides to originate a loan successfully and credits the customers bank account. Deposit creation in essence is what leads to creation of new money.

But taking a step back to what even leads to the creation of a deposit? As posited before, lending begets deposits and lending in itself is predominantly demand side driven. Customers might come knocking on the doors of several banks and if they happen to meet the credit worthiness criteria of that institution, the bank is usually willing to extend a loan. To begin with and to clear the air, what does not happen in this process?

The bank does not scour for deposits it might have received from customers.

It does not engage in identifying deposits that it can then match up against the loan and provide the funds to the borrower.

It does not identify deposits to the tune of 5 or 10% of the loan to be handed out and then make the loan. This is what we define as fractional reserve theory where the bank only needs 10% of the loan amount in reserves to be able to make the loan.

Back to the lending process and what materialises during the process. When the bank agrees to make the loan, it essentially credits the account of the borrower. This loan leads to money being deposited in the customers account. The customer now has an asset in the form of deposit received from the bank but at the same time an equivalent liability in the form of a loan that has to be paid back.

For the bank, it has an asset in the form of a loan it has made to the customer and a liability in the form of an account that the customer owns which holds the deposit that they can withdraw any time. This deposit is an IOU on the bank that has made the loan.

This exact breakdown is also visible in the form of the stacked graph that the Bank of England created in highlighting the money creation process post a loan being made to a consumer.

What is of utmost importance to the bank is what happens post creation of deposits in a customers account and having recorded entries into an accounting journal. Ideally, the bank who has just lent out the amount to the customer would want that customer to continue banking with them. That is a happy path scenario. The scenario that every bank has to prepare for eventually is where the borrower eventually transfers the whole amount to what might be their primary bank account or slowly pulls money out as they start spending. For any inter-bank transfers, there is a settlement process that the banks engage which involves Central Bank Reserves. Nowadays, settlement primarily happens with banks via accounts they hold with the Central Banks and the reserves they hold in those accounts. At this stage of the process, liquidity management comes into play and this whole process is what is of absolute essence to maintain a well functioning and trustworthy institution.

There are several ways that a bank can fund their liquidity needs but 3 that play a significant role(U.S focussed) are

Retail

These are deposits that households or businesses end up keeping with their bank in a checking/current account. The expectation of any return on the funds kept with the bank are next to nothing and this could be either because of wanting convenience by storing their money given their trust/branding of the bank or in accessing other bank products at a discounted rate(accomplished through cross-subsidisation)

Another reason around the low cost of retail deposits revolves around what is called the deposit beta. The beta measures how sensitive are the banks deposit base and the costs associated to a change in the interest rates set by the Federal Reserve/Bank of England. A 0.5 deposit beta implies that as the Fed has raised rates by 5% over the past 18 months, the bank would have had to only increase the interest it offers to customers by 2.5%.

Even though there is an inherent cost associated in attracting retail deposits, the strategy for most banks have always been to diversify its deposit base to create more stability but at the same time ensuring access to various different types of funding sources. Retail deposits whether they were created by the bank in the process of lending or having received them given a customer transferring them from one bank to another have to always be thought of as a borrowing. I highlight this because deposits are an IOU from a bank to a customer and are always fully owned by the depositor but controlled by the bank because of the trust endowed upon them.

Wholesale

This type of funding can encompass FHLB advances, brokered deposits, repos, raising debt etc. Even though there are several options available to banks to avail such funding, they usually come at a higher cost vs the retail deposits and in almost all cases require some form of collateral for the bank to put up.

Central Banks(Federal Reserve in this case)

Banks not only have the option of borrowing from one another through the Fed Fund markets but can also avail funds directly from the Federal Reserve over short periods especially if it means settling any outstanding payments in the form of Central Bank Reserves

The reason for highlighting liquidity management is to lay bare to the fact that a bank largely has a clear view on its liquidity needs and makes loans with that information in mind. If it does find itself in a situation where there are significant outflows from the bank, it specifically has on hand Wholesale and Central Banks funding options to leverage upon.

Now, one might say at this point that if banks create money, why not just go ahead and create money out of thin air? Some people might see fractional reserve theory and the presence of reserve requirements as the answer. To use Fed and BoE as examples, as of 2020, Fed does not have reserve requirements anymore(See Fed policy tool page) and bank deposits can be moved to Central Banks if needed to build on reserves. UK where I currently reside does not have reserve requirements and and up until a few decades ago, Bank of England would work with banks individually to determine reserve requirements but that was scrapped.

The ability of a bank to create deposits out of “thin air” are contingent on the trust that an entity on the other side holds. This entity can be a consumer/business holding deposits which are an IOU from the bank. It could be others that have lent money to the bank. Without this trust in the bank, the deposits it creates aka the IOUs have no meaning and are absolutely worthless. It was this situation that SVB found itself in. The IOUs in the form of deposits held by customers immediately fled once the trust in the bank disappeared. Therefore the expectation that SVB could just create money out of thin air or so be the case for any bank is a fallacy as it is completely contingent on what the other person does with the deposits created. If they choose to move their deposits, the bank has to determine the liquidity mechanism as described above to find a way to settle the transfer.

To bring the idea of credit creation theory to a close, here is what the Federal Reserve concluded in their paper

At this point, we feel reasonably confident that there is little evidence that open market operations can directly change loans by changing deposits. It must be the case, however, that as assets on a bank’s balance sheet change, liabilities must also change. A more plausible channel is that the quantity of loans is primarily determined by the demand, which is presumably a function of price and other economic variables, subject to the borrower meeting the criteria set forth by the bank. To fund these loans, banks have a set of liabilities that they can adjust in reaction to shifts in the demand for loans.

The role of reserves and money in macroeconomics has a long history. Simple textbook treatments of the money multiplier give the quantity of bank reserves a causal role in determining the quantity of money and bank lending and thus the transmission mechanism of monetary policy. This role results from the assumptions that reserve requirements generate a direct and tight linkage between money and reserves and that the central bank controls the money supply by adjusting the quantity of reserves through open market operations. Using data from recent decades, we have demonstrated that this simple textbook link is implausible in the United States for a number of reasons. First, when money is measured as M2, only a small portion of it is reservable and thus only a small portion is linked to the level of reserve balances the Fed provides through open market operations. Second, except for a brief period in the early 1980s, the Fed has traditionally aimed to control the federal funds rate rather than the quantity of reserves. Third, reserve balances are not identical to required reserves, and the federal funds rate is the interest rate in the market for all reserve balances, not just required reserves. Reserve balances are supplied elastically at the target funds rate. Finally, reservable liabilities fund only a small fraction of bank lending and the evidence suggests that they are not the marginal source of funding, either. All of these points are a reflection of the institutional structure of the U.S. banking system and suggest that the textbook role of money is not operative

Richard Werner even went to the lengths of testing the hypothesis of credit creation out with small German banks. High level summary of what he set out to do

The simplest possible test design is to examine a bank's internal accounting during the process of granting a bank loan. When all the necessary bank credit procedures have been undertaken (starting from ‘know-your-customer’ and anti-money laundering regulations to credit analysis, risk rating to the negotiation of the details of the loan contract) and signatures are exchanged on the bank loan, the borrower's current account will be credited with the amount of the loan. The key question is whether as a prerequisite of this accounting operation of booking the borrower's loan principal into their bank account the bank actually withdraws this amount from another account, resulting in a reduction of equal value in the balance of another entity — either drawing down reserves (as the fractional reserve theory maintains) or other funds (as the financial intermediation theory maintains). Should it be found that the bank is able to credit the borrower's account with the loan principal without having withdrawn money from any other internal or external account, or without transferring the money from any other source internally or externally, this would constitute prima facie evidence that the bank was able to create the loan principal out of nothing. In that case, the credit creation theory would be supported and the theory that the individual bank acts as an intermediary that needs to obtain savings or funds first, before being able to extend credit (whether in conformity with the fractional reserve theory or the financial intermediation theory), would be rejected.

The paper is extremely detailed and goes through the history of the economic beliefs, the time frame, and where we stand currently but given the success of the experiment he ran, the conclusion was stated as follows -

The second contribution of this paper has been to report on the first empirical study testing the three main hypotheses. They have been successfully tested in a real world setting of borrowing from a bank and examining the actual internal bank accounting in an uncontrolled real world environment.

It was examined whether in the process of making money available to the borrower the bank transfers these funds from other accounts (within or outside the bank). In the process of making loaned money available in the borrower's bank account, it was found that the bank did not transfer the money away from other internal or external accounts, resulting in a rejection of both the fractional reserve theory and the financial intermediation theory. Instead, it was found that the bank newly ‘invented’ the funds by crediting the borrower's account with a deposit, although no such deposit had taken place. This is in line with the claims of the credit creation theory.

Fintechs and democratisation of access to high yield products

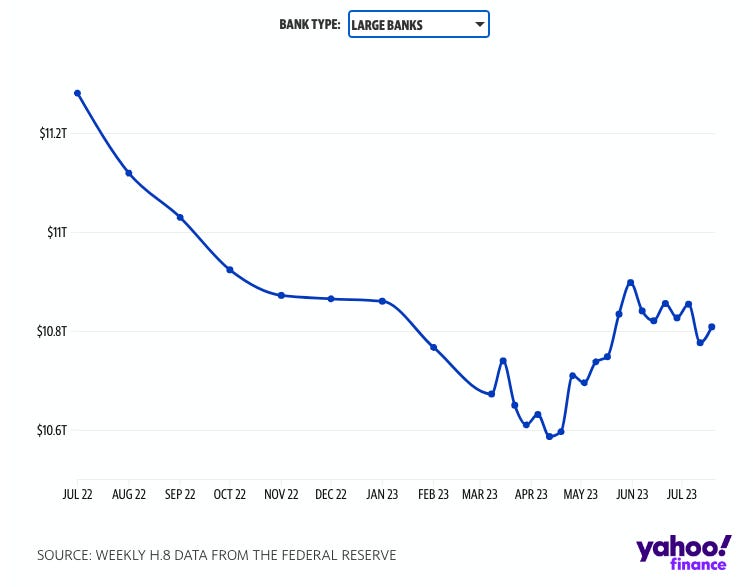

With the onset of covid, the monetary and fiscal stimulus over the next year was so massive that the long term trend completely buckled. To highlight the size of the stimulus and impact on deposits, I stretched the data back to 2008 and the GFC time period.

The fiscal and monetary stimulus completely upended the long term deposit growth by flushing the system with immense amount of liquidity. I don’t mean to turn this into what really led to the inflationary pressures but what has happened over the past 18 months is that Central Banks including Federal Reserve have raised rates at probably the fastest rate in over 40 years(going back to the early 80s inflation crisis) to finally curtail that growth.

The main way that Central Banks control or put a constraint on creation of money in the economy is through the monetary policy especially the interest paid on reserves. As highlighted before, lending being largely a demand side issue, rising rates increases the floor of the rates that the consumers will have to pay and thereby has an effect of reducing demand for loans.

With most banks running a deposit beta < 1 would imply that the increase in rates offered on customer deposits has been much lower. This is evident in the image below which shows average Net Interest Margin for institutions unto $1T in assets

Though I personally believe that we are probably seeing the top when it comes to banks and their NIMs. The Fed fund rates set by Federal Reserve ends up being a floor to what the banks will accept for any risk they take in terms of originating a loan. If they are able to get 5% risk free by parking their reserves with the Fed, then the cumulation of that alongside the credit, liquidity, and macro risks that they might face in making a loan will lead to the rates being higher than the base rate.

With this increase in rates, the demand for loans from consumers is bound to fall as people end up making decisions on what is absolutely important for them now vs what they can push in hopes of delayed gratification. With the demand side taking a hit, the ability to turnover the asset side continuously to higher yielding loans for banks becomes harder. At the same the consumer expectations on deposits they hold at banks and the rate of return that starts getting baked in continues to increase. This is where fintechs come into play. Over the past year, the average yield on savings accounts(at banks) has continued to increase and combining with a lower loan demand, the expectation is that as the next couple of quarters play out, we might see the Net Interest Margins top out and start their downwards trajectory.

The second issue and what was responsible for bringing down Silicon Valley Bank and First Republic amongst others was what these banks were holding on the asset side of the balance sheet. In having invested in longer duration securities and being on the wrong side of the interest rate hikes, the accounting markdowns on the held-to-maturity securities meant that the banks have been staring at massive losses. This eroded the trust in these institutions and deposit flight that ensued.

A bank in this situation could entice would be borrowers and demand for loans by potentially offering loans at a lower rate than the competition. Though if this is done in isolation of not fixing deposit flight, it only worsens the issue. Therefore to tackle the other side of the trade, at the same time the bank would have to entice either the same borrower or other customers with higher interest rates on their deposits. Either way, the bank that finds itself in this situation faces a lower NIM and therefore reduced profitability no matter what path it takes.

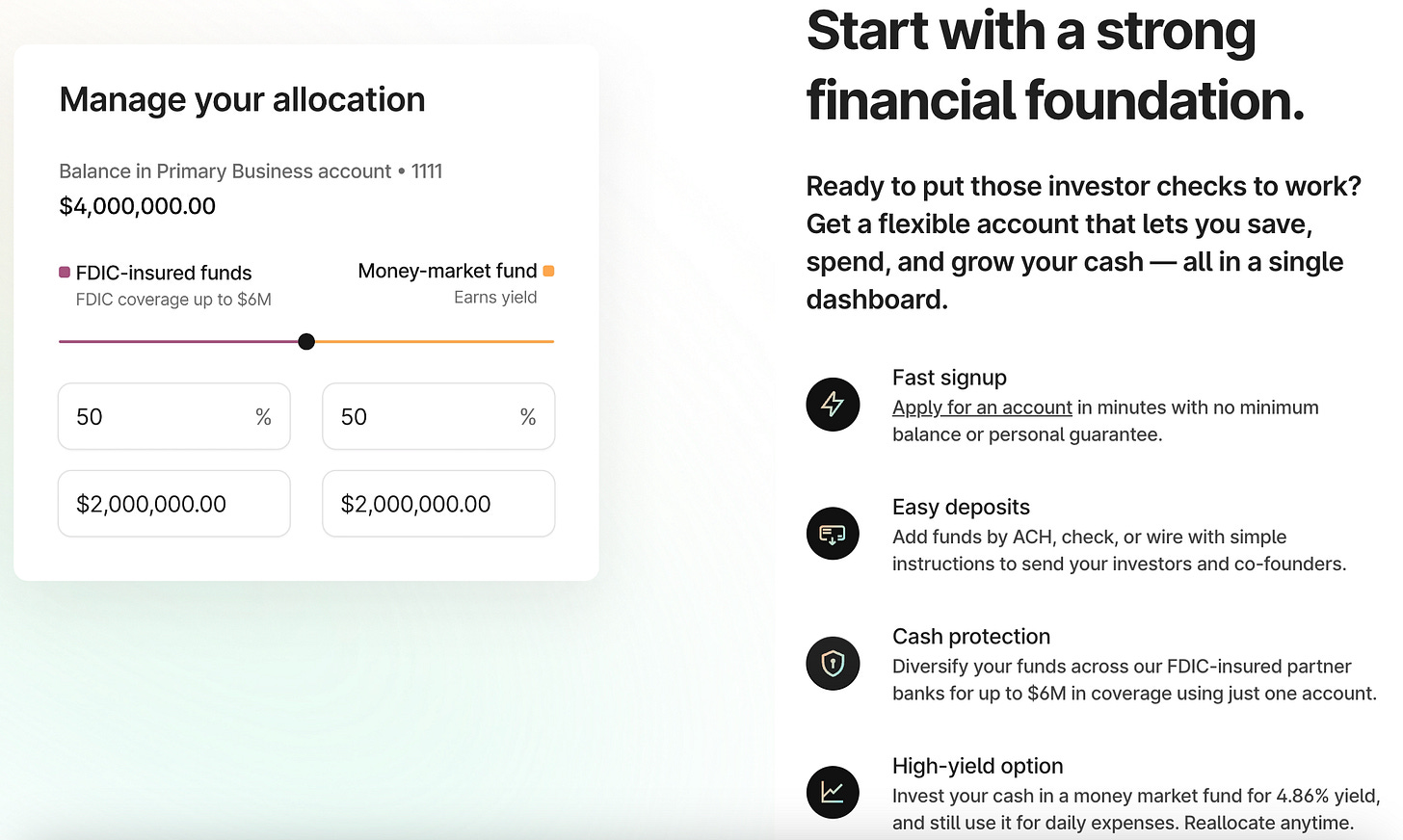

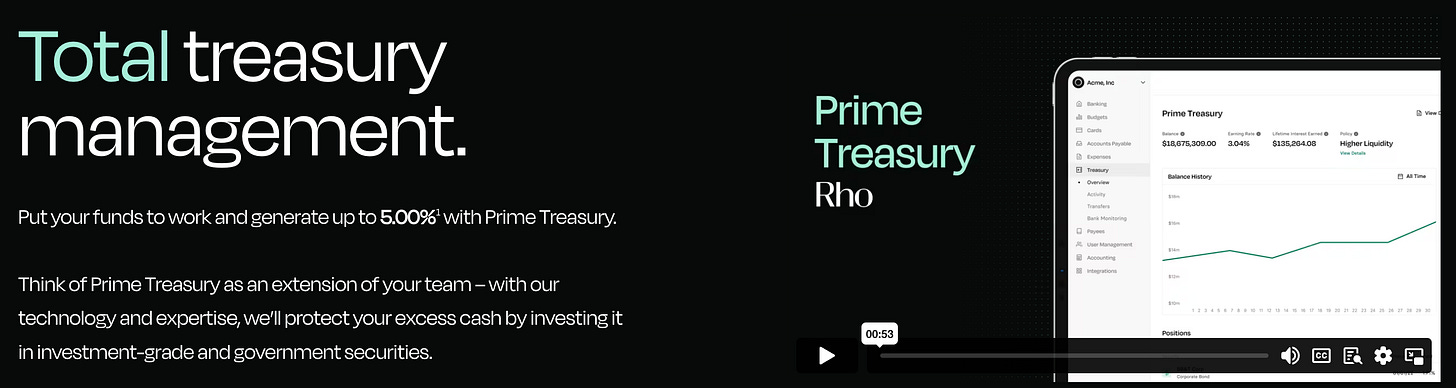

Finally, comes the competitive aspect especially with the role that Fintechs have been playing. My focus will specifically be on the products that Mercury, Brex, Rho, and Meow have rolled out in serving and helping customers access interest rates that track the Fed Fund rate. With deposit contraction and pressure especially for the small/mid-sized business, there is an ever increasing pressure on how to attract deposits as the main mechanism given their relative cheapness vs securing wholesale funding.

Fintechs that usually partner with banks to be able to offer their services have been able to launch high interest rate products that they are offering to their own customers. This is visible through the nearly $2T that have flown into the overnight reverse repo facility that the Federal Reserve created in mid 2010s

Not all of the above volumes are coming from fintechs but what has happened over the past year is the democratisation of access for any SMB that finds itself interested in availing treasury services through these neobanks.

Not going into the specifics around the strategy on how each of these products fit into the overarching product suite offered by each of the neobanks, I find it immensely interesting how these fintechs(a big caveat and firm I am not mentioning that does this for both consumers and businesses is obviously Wise. I work for them and will probably one day dedicate a whole post on the work being done by the folks at the firm) have taken a disadvantage which is lack of banking license and turned into a structural advantage in attracting customers by being completely transparent on pricing and in allowing businesses to benefit immensely on rates that they can get via access to Fed facility. In offering high interest rate products given that they are not really stymied by the liquidity management issues that might plague a bank reminds me of one of favourite Ben Thompson article on strategy credit

This competitive pressure materialises in 2 ways for banks. First, for any deposit that is not sticky enough and in the lookout for yield especially when rates are lurking around 5%, it becomes immensely competitive for banks to have to determine ways to keep these customer relationships and deposits.

Second, the combination of competitive pressures and flight to safety(whether MMFs or big banks) has meant that small and mid sized banks are having to work harder to keep their customers.

The big banks flushed with excess cash savings in the form of deposits have intentionally let these deposits flow out to ease any pressure on their profitability. This policy took a turn as the big banks inadvertently ended up being on the recipient side of deposit inflows post SVB crisis in march/april.

Third, if the deposits itself cannot be thought of as sticky enough when generated either through lending or in having attracted someone else’s customers before, banks will have to increasingly start depending on wholesale funding. In some way this is already visible in the rapid increase in usage of brokered deposits.

U.S has seen nearly 2 decades of near 0% interest rate that led to customers clamouring for yield through asset purchases whether it was stocks/bonds/crypto/real estate/private equity etc. Now with interest rates at their highest level since 2006 and with more potential interest rate increases to come, fintechs are paving the path to launching products for both personal and business consumers that give them access to these interest rates. This is reminiscent of MMFs in late 70s and early 80s. Here is what SEC highlighted in one of their papers

MMFs date back to 1971 when the Reserve Primary Fund was launched. MMFs experienced their initial period of rapid growth in 1974 and early 1975, as a result of Regulation Q’s strict ceiling on the interest rates that insured depository institutions were permitted to pay to depositors. In the high interest rate environment that existed during this period, money market rates of return rose well above the ceiling on interest that could be paid on deposits accounts. In order to outpace interest and achieve returns higher than those fixed by Regulation Q, many customers withdrew their assets from deposit accounts and placed their funds into money market mutual funds.

Explosive growth in MMFs occurred again in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when very high money market rates produced large differences in the rates of return being paid by MMFs and depository institutions and as a result MMF assets rose rapidly from $4 billion in 1977 to $235 billion in 1982.

In order to help banks compete with MMFs, in 1980 Congress passed the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act (the “DIDMCA”), which created a committee charged with phasing out Regulation Q’s limitations on interest and dividends paid to depositors by 1986. Two years later, Congress passed the Garn-St. Germain Depository Institutions Act, which directed this committee to provide depository institutions with an account that would be “directly equivalent to and competitive with money market mutual funds.” These accounts, known as money market deposit accounts (MMDAs), had no limits on the interest depositors could earn. Both the instructions of the DIDMCA and the moniker chosen for these accounts indicate that they were designed in order to allow depository institutions to better compete with MMFs

Regulatory arbitrage then was taken away that allowed banks to offer and compete at a level playing field. What the banks face now is not an inability to offer these products but what is the level of pain they are willing to face when it comes to taking a hit on their profitability?

I claim to have no foresight on where interest rates might be but we have a whole new industry in fintechs that was non existent 2 decades ago. These firms find themselves with tight belts and controlled spending while looking for a path to profitability. Why not attract customers by offering them a wedge product in high interest rates and savings?

To bring it all together, money creation might predominantly lie with banks but there are certainly guardrails around that process. For as easy it might be to create an accounting entry and create deposits out of thin air, it is of absolute essence for the small to mid sized banks to think through

How are its deposits or IOUs perceived in the market? Does it perceive its customers to be sticky enough so as to not worry about deposit flight?

What structural advantages does it have when it comes to lending operations? If these advantages come from underpricing to gain demand from customers without necessarily having an underlying system that grants it a lower cost, how sustainable is this?

With the competition for deposits heating up and probably to stay at a level where fintechs provide access to much better returns, how do banks continue to attract deposits to ensure they have liquidity? If not for retail deposits, what does access to wholesale funding look like and how does that bake into its Net Interest Margin?

I hope you enjoyed reading this post. I can be found here on Linkedin and Twitter. If you have any comments or suggestions, I would love to hear them either on there or in the comments below.

Thank you for reading!